The year was 1850, and many people were heading to the midwest for a new opportunity in life. Large and small wagon trains gathered, thinking there was safety in numbers.

At this time in the western territory, Indians had lived, and survived there for many years, but some were not always welcoming to newcomers. With more and more wagon trains moving through there every day, some tribes were willing and able to trade items they had for food and wares. Meanwhile, some made sure that the people in the wagon trains were not accepted, but were killed or maimed for what they had.

On one of these wagon trains was the family of Royce and Mary Ann Oatman. They traveled with seven children, ranging in ages from one to seventeen. They had left the Mormon religion in Utah to join another religion called Brewsterites. James Brewster formed this religion and also led the wagon train consisting of 90 followers, and across the territory they traveled, all was well, for a while. Meanwhile as they traveled on, dissention arose between some families and Brewster. Royce Oatman was one, so nearing Santa Fe in New Mexico, they decided to split from the wagon train and go south. As the new path was being forged they stopped in New Mexico and realized the climate and terrain was to rough to live in and continued to Maricopa Wells, Arizona. Although they were warned about the trail ahead being rough and possessing hostile indians, they foraged on. He split once again and this time with only his family in tow he proceeded.

Massacre on the Banks of the Gila River

February 18, 1851, and tired of traveling, the Oatmans stopped by the banks of the Gila River in the state of Arizona. Soon events put that stop over as the last place the whole family was together.

Following is an article written about that day in the Mohave County miner and our meneral weath newspaper. The author is an historian of Arizona, James H. McClintock, and this is his account of that day.

“One of the most notorious features of Indian warfare was the murder of the Oatman family, at whatever since has been known as Oatman Flat.” Furthermore he states, ” The food supply was getting low, and the Indians themselves had little. The Indians were given food, and in return they stabbed the mother and father to death. The infant child was stabbed with a spear. The son, Lorenzo, 15 years old, was clubbed and thrown over a rocky point, with the assumption that he had been killed. All others except Olive Oatman, 16, and Mary Ann, age 7, were killed. The two girls were taken captive by the Indians”.

Being Marked as Indian Property

Olive and Mary Ann were held as slaves at a village near the site of modern Congress, Arizona. Next came the abuse and Olive feared the outcome would rival what happen to the rest of her family. As slaves they had to forage for food, carry water and firewood, and other menial tasks. They were beaten and starved.

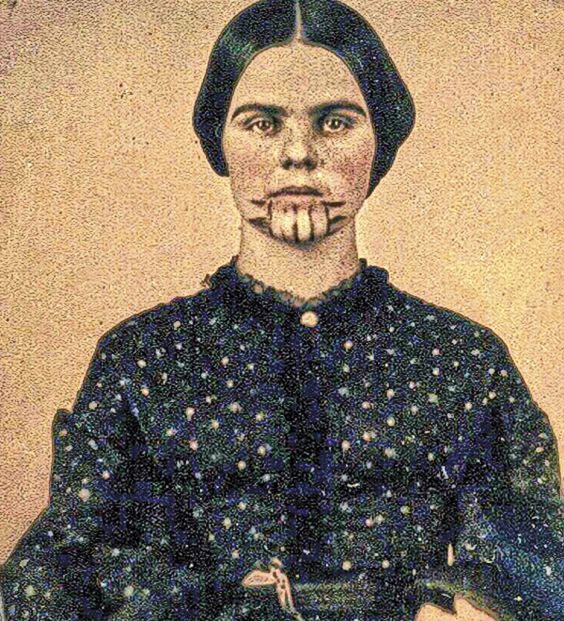

A year later they were traded to a group of Mohave Indians. In return, their first captors received, two horses, vegetables, blankets and other trinkets.

In their new home they were made to feel like a part of the tribe. To fit in with the other women of the tribe they first had to be marked. Each girl was tattooed with indelible blue cactus lines on their chins. With this they would always be known as the girls with the blue tattoos. How may you ask did they tattoo a person back then without the tools we have today? American Indians tattoos were applied by the use of a sharpened bone or rock. They pricked the skin, and the design scratched in. They would use natural dyes from plants, or soot. The girls were treated just as the rest of the Indian women. It has been summarized that Olive may have been married off to one of the Indians and had children, but it was never proven.

The Beginning of the End.

In 1855, a severe drought hit, and the food supply dwindled. Mary Ann Oatman, age 11 would depart from this world due to starvation, along with many Mojave people.

During this time a request came from Fort Yuma, in California; to the Mojave. They had been approached by other white settlers telling them that a white girl was being held captive with the tribe. The commander at the fort demanded her return. The Mojave hid Olive and ignored the request. The commander was persistent. The Mojave Indian chief then said that they had no white girl, only tattooed women of the tribe. He assured the commander only Indian women had these markings to prove they belonged to that tribe. No white women would be branded.

During all of this, a surprize person arrived at the fort, Olives’s brother Lorenzo. Lorenzo who had been thought dead, but still lived, had heard that his sister may also still be alive and wanted her released from the Indians. The Chief of the Mojave finally and with Olives consent, [ because of living with them for so long she was afraid to leave ] was ransomed, and escorted to Fort Yuma to reunite with her brother.

When she arrived at the fort, she insisted that she be given proper clothing because she only wore a skirt and no top. She spoke Indian better then she spoke English, and she had a tattoo that no other white woman had.

She reunited with her brother Lorenzo, and the meeting made headlines in all the papers across the West.

Living the White Life

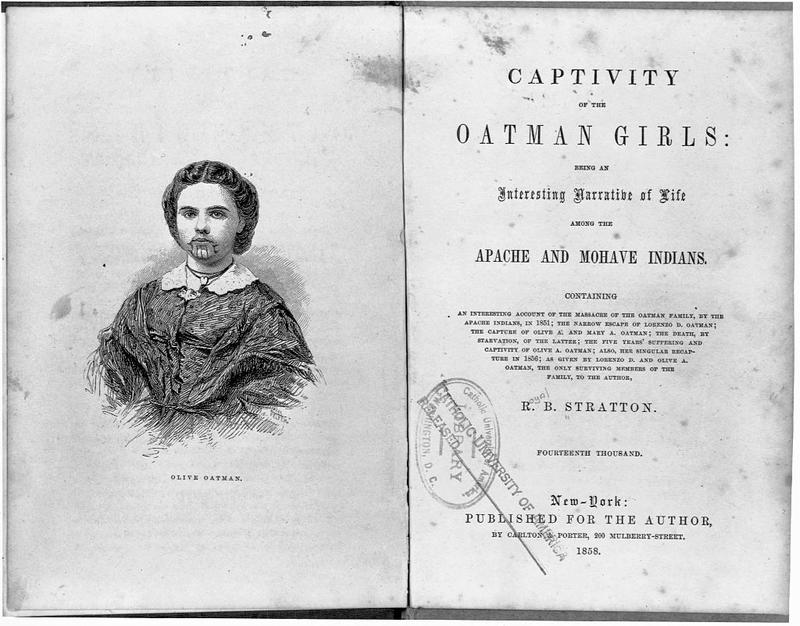

Olive moved with her brother to New York. A book was published about her ordeal, Life Among the Indians: Captivity of the Oatman Girls. It was written by Reverend Royal Stratton, and he and she toured the country and gave lectures to promote the book.

Not wanting to be stared at all the time because of her tattoo, she wore a veil to conceal it. When giving a talk and asked why she had been branded, she replied “The Mojave tattoo their captives so if they escape they would easily be recognized when they were found. She didn’t tell them that all Indian women were marked also in the Mojave tribes. Royalties from the book afforded Olive and Lorenzo an education that they had been deprived of.

In 1865, Olive married, and moved to Detroit, Michigan for seven years, before moving for the last time to Sherman, Texas. Her husband, John Fairchild, became president of the City Bank there. It is said that he did not care for the book that had been written about his wife’s life, and found and burned as many copies as he could.

Olive rarely ever talked about her youth or time with the Indians in later life. Olive Oatman Fairchild died of a heart attack in 1903, at the age of 65. She had lived a life full of happiness, and sorrow, terror and peace, and many experiences in between before her death. She was buried at the West Hill Cemetery in Sherman, Texas.

The site of her family’s attack, became Oatman, Arizona, and has a plaque there to tell of the massacre. The girl with the blue tattoo survived an ordeal that many never got or wanted, and with her story, she has made a mark on our history!